Opening

Friday October 8 at 5pm, 2010

Duration

October 8 till October 29, 2010

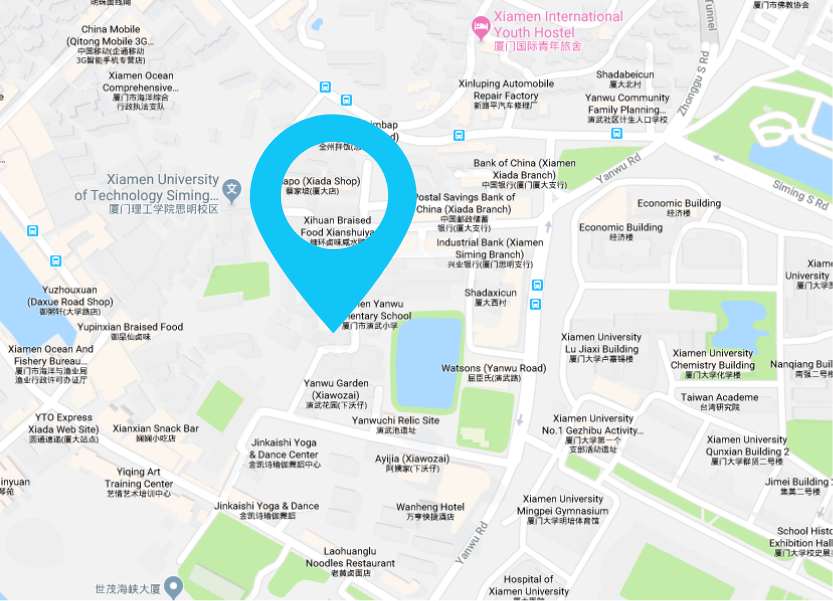

Location

CEAC, Xiamen, China

Artist

In Brancusi’s Psychosis Maddy Arkesteyn investigates a new escape route from oppressive ways of looking at things. Her sculptures are an architectural recreation of spaces using ropes. These ropes become textile columns, swaying totem poles, Chinese lanterns with holes… They refer to long ago, faraway and yet nearby.

In Brancusi’s Psychosis Maddy Arkesteyn investigates a new escape route from oppressive ways of looking at things. Her sculptures are an architectural recreation of spaces using ropes. These ropes become textile columns, swaying totem poles, Chinese lanterns with holes… They refer to long ago, faraway and yet nearby.

It is an architecture that accommodates entropy; it is a system that acquires form and meaning from the degree of chaos and degeneration. Arkesteyn spends hundreds of hours knotting vertically hanging strands in such a way that patterns are created. She doesn’t conceal the detail. She loses herself in her handiwork. Her only tool is her hands, her only knot is the flat knot. She loses herself in a knot.

These maniacal operations gradually produce knotted sculptures. Next to each sculpture another is created, and then another. They overrun any existing idea of unity. They form a mental landscape. Just as in a psychosis contact with the real environment is lost, so too Arkesteyn sets an expanding network in motion. She dislodges all structure by performing decisive operations.

Macramé, it’s called. And the mere mention of the word immediately clarifies the many layers of meaning Arkesteyn explores and her resistance to prevailing forms of sculpture. She uses macramé, an ancient knotting technique but, to confuse the issue, one which became synonymous with women’s handicrafts in the 1970s. She strips the technique of its limited cultural connotations and at the same time zeroes in on it. She uses it to build fabric cathedrals. Sometimes she has young girls to walk through them, like living statues which represent an ideal. The spectator is given the choice between making his way between the sculptures or staying outside. Her installations are contemporary cathedrals.

For the late-medieval cathedral builders the surveyable scope was not that of a closed habitation. Perspective had to be infinite. The trivial was not trivial, the scope and the limitation of existence went hand in hand with the universality of that existence. In building, they were committed to the infinite, the relevant, the essence. Inside was outside and outside was inside. That is what Arkesteyn is: a builder of cathedrals. That is what Arkesteyn does with her sculptures: geometry with macramé, geometry which leads to the transcendental.

Or as the artist Constantin Brancusi to whom she refers in her title said: “Art does not represent ideas but generates them, which means that a true work of art comes into being intuitively, without preconceived motives because it is the motive.”